We recently finished The Queen’s Gambit, a seven-episode series about a chess prodigy who discovers her talent in an orphanage, visualizing complete games on the ceiling under the influence of tranquilizers. Although certainly about various addictions, it was not only uplifting without being maudlin, it actually played against common themes by not resorting to abuse or violence for a cheap emotional sting. Instead, it let the complex character relationships—and how they overcome personal obstacles—carry the narrative, without resorting to the blame game. Maybe the last part felt more credible as the show faithfully displayed the affectation and decor of the late fifties and early sixties, as opposed to the age of victimhood we currently inhabit.

That led to a search of the author of the eponymous book it was based on, who I’d not heard of, Walter Tevis (1928-84). Tevis has the unusual fact of having four of his six novels made into film. The earlier three are well-known: The Hustler (1959, film made in 1961); The Man Who Fell to Earth (1961, film 1976); The Color of Money (1984, film in 1986); with The Queen’s Gambit published in 1983. The large lacuna between the success in his 30’s and the productivity near the end of his short life is basically due to a protracted struggle with alcohol addiction and isolation, a theme that recurs in all his work.

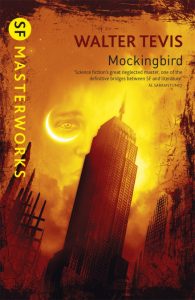

Surprisingly, not all of his books are in print, but I managed last week to find the one not-terribly-expensive paperback of Mockingbird, his cult SF classic published in 1980, drawn to the title because it is the name of the CIA media infiltration and control program essential to maintaining a pliant population. Besides it being a top tier SF book, it is thematically and chillingly relevant to some of what is occurring now. This is why books will always be important, and why great writers need our support, even after they are gone.

Mockingbird takes place in 2467, 500 years after the Summer of Love, which it is in a sense the antipode to. Likely this was intentional. Reading has been eliminated for generations, NYC is run by “moron robots”—their intelligence is limited to the basic jobs they do—with a few higher level robots who can act as a judge, physician, or (surprise) politician. What humans are left exist on a diet of synthetic food and tranquilizing “sopors”—soporifics—with nothing essential or creative to do, mostly numbly watching 3D TV of endless sex, violence, and a combination of the two. In other words, a hell of addictions enabled by some sort of credit card universal income.

Not to get too boiled down in plot, there are a couple of prescient aspects to this book. The world here is basically one where the social distancing enforced today has played out over centuries and become codified and embodied. People are not raised in families, but in dormitories. No family life at all. In fact, co-habitation is a crime. People are entranced and circumscribed by slogans regurgitated throughout their lives: “Don’t ask, relax” (and take another sopor); “quick sex is best” (no intimacy, no eye contact, no conversation). People recoil from touch. “Privacy” is as enshrined as our Bill of Rights (used to be). There is little difference between the “moron robots” and the moron people. When faced with anyone doing something mildly out of the ordinary, their reaction is to play kapo-snitch and turn each other in to robotic “Detectors” (mask Nazis and contact tracers rejoice!). But, even the robots cower when challenged, and the human snitches just pop a few sopors and move along. As most of us are all feeling viscerally, tyranny depends on compliance.

Cannot help but be reminded of the large number of the young male population in Japan, where this seems to be clinically prevalent, who recoil from any live conversation, especially with women, and who prefer the soulless grind of robot sex and porn: only cyber simulacrum intimacy is possible. Thus the population declines.

In Mockingbird the solution for the two awakened characters is literacy. Benchley learns to read and write by watching silent movies and transcribing them. When he finds a dictionary it is the Rosetta Stone. There is added joy in these old movies as they include romance, emotional expression, family and—kissing! He finds Mary Lou, a woman who escaped the dormitories and the infertility-inducing sopors, living by her wits at the Bronx Zoo (where all the animals and all the children eating ice cream watching them are robots). They fall in love through learning to read the few books they can scavenge to each other, and by writing their own story.

The third protagonist is Spofforth, the last of the human-robot hybrids. “Spofforth” is a name that begs decoding, but other than “sopor” being in there, or something unhelpful like “spoof-forth”, I could use some help. Spofforth is hundreds of years old, and the only remaining version whose brain circuitry is copied from an actual unnamed brilliant human, excepting identity and memories. Still, he has dreams and snippets of poetry bleed in.

Spofforth cannot forget anything, is self-repairing (thus theoretically eternal), and runs NYC because no one else can abate the entropic systemic decay. He is the apotheosis of the AI dream. Yet Spofforth only desires one thing: to die. Yet he cannot, because his programming forces him to work with humanity as long as it exists. When he tries to kill himself his programming freezes him. Thus the hell awaiting all the drooling transhumanists (“And what could be closer to living death than aspiring to have your consciousness transistorized and encased in heavy metal?” Katabatic Wind).

Spofforth, who is willing to kill off humanity in order to be allowed to die, exhibits what is called ‘the banality of evil’. We, as a culture, as a country, as individuals, as spiritual beings ensconced in our peculiar 3d projection through our sensorium, are staring down our extinction as any of those things. The way through it is discriminative discernment, and reading great works fosters that. Especially in the analog paper versions. You can glean information and a few ideas from videos, but they mostly elicit parroting mockingbirds. Literature inculcates imagination, a higher level of being than logic and emotion. Read for the joy of it, knowing that all our lives depend upon it.